Choosing “the better battery” sounds simple until you notice that people often compare two things that aren’t actually opposites. “Lithium battery” refers to a chemistry family (most commonly lithium-ion or lithium iron phosphate), while “high capacity battery” describes a performance attribute (how much energy a battery can store). In other words, a battery can be lithium and high capacity at the same time. The real question is usually: Should I prioritize lithium chemistry, or should I prioritize maximum capacity (often at lower cost or different chemistry), given my use case? This article clears up the confusion and helps you decide based on safety, lifespan, cost, power demands, charging behavior, and practical scenarios.

Understanding the Terms: Lithium vs. High Capacity

A battery’s capacity is typically measured in amp-hours (Ah) or watt-hours (Wh). Amp-hours tell you how much current the battery can provide over time at a given voltage. Watt-hours tell you the total energy stored, which is generally the best comparison across different voltages.

A lithium battery usually means:

A high capacity battery might mean:

-

A larger battery pack (more cells in parallel/series) regardless of chemistry.

-

A chemistry with high energy density (often lithium-ion).

-

Or sometimes a marketing label applied to lead-acid, nickel-based, or lithium batteries.

So when someone asks which is better, they usually mean one of these comparisons:

-

Lithium vs. lead-acid for the same application.

-

Lithium vs. “bigger capacity” (e.g., larger lead-acid bank) under a budget limit.

-

High capacity lithium vs. standard capacity lithium (which is a sizing decision, not chemistry).

The Core Trade-Offs That Actually Matter

The “best” choice depends on what you care about most.

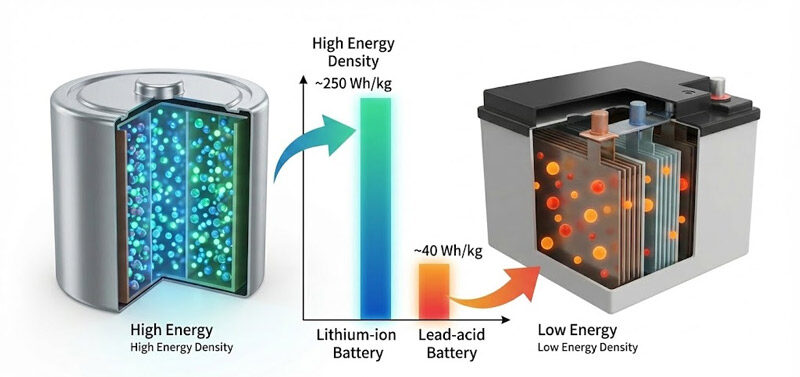

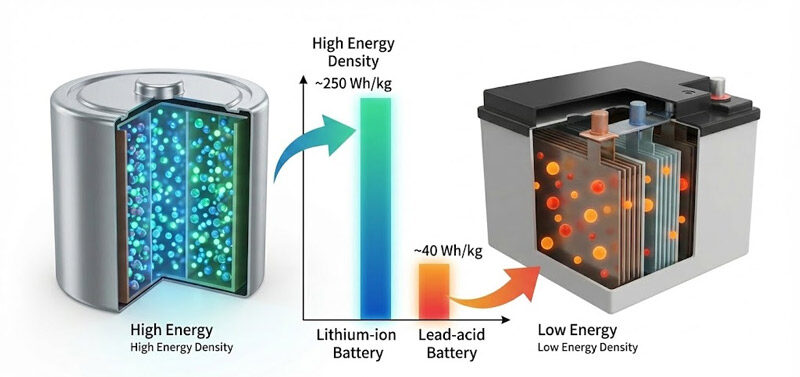

Energy density and weight: Lithium batteries typically store more energy per kilogram than lead-acid. If you need portability (e-bikes, handheld devices, drones) or you are weight-limited (marine, RV, aviation-adjacent systems), lithium’s advantage is hard to ignore.

Usable capacity: Many non-lithium chemistries (especially lead-acid) should not be deeply discharged routinely without significantly reducing lifespan. That means a “high capacity” lead-acid battery may not deliver all of that capacity in real use. Lithium batteries can often use a larger fraction of their rated capacity without the same penalty, so usable energy can be higher even if the nameplate numbers look similar.

Power delivery and voltage stability: Lithium tends to hold voltage more consistently during discharge, which helps devices run reliably and efficiently. Lead-acid voltage sag can trigger low-voltage cutoffs earlier and reduce performance under high loads.

Cycle life: Lithium (especially LiFePO₄) can last far more charge/discharge cycles than typical lead-acid under comparable depth-of-discharge conditions. For daily cycling—solar storage, off-grid systems, fleet devices—cycle life becomes a major economic factor.

Charging speed and efficiency: Lithium can usually charge faster and more efficiently. Lead-acid often requires multi-stage charging and can be slower to reach full charge, especially the last 10–20%.

Safety and temperature behavior: Lithium batteries require proper management (often a BMS) to prevent overcharge/overdischarge and handle cell balancing. Some lithium chemistries are more thermally stable (LiFePO₄) than others. Lead-acid is generally tolerant and simpler, but it introduces different hazards (acid, hydrogen gas during charging, ventilation needs).

Upfront cost vs. lifetime cost: Lithium often costs more upfront. But when you factor in longer life, higher usable capacity, and better efficiency, lithium can be cheaper over the long run in many heavy-use scenarios.

Comparison Table (Typical Characteristics)

Note: Values vary by manufacturer and design; the table reflects general, commonly observed tendencies.

|

Factor

|

Lithium-ion (Li-ion)

|

Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO₄)

|

Lead-Acid (AGM / Flooded) “High Capacity” Bank

|

|

Energy density (weight efficiency)

|

High

|

Medium-High

|

Low

|

|

Usable depth of discharge (practical)

|

High (often 80–90% usable)

|

Very high (often 80–100% usable)

|

Lower (often 30–50% recommended for long life)

|

|

Cycle life (typical)

|

Medium-High

|

High to very high

|

Low to medium

|

|

Voltage stability under load

|

Good

|

Very good

|

Fair to poor (more sag)

|

|

Charging speed

|

Fast

|

Fast

|

Slower (especially near full)

|

|

Charging efficiency

|

High

|

High

|

Lower

|

|

Maintenance/ventilation

|

Low

|

Low

|

Can be higher; ventilation may be needed

|

|

Cold-temperature charging

|

Needs care; may require restrictions

|

Needs care; many LFP packs limit charging in cold

|

Generally more tolerant (still reduced capacity in cold)

|

|

Upfront cost

|

Higher

|

Higher

|

Lower

|

|

Best fit

|

High energy, compact electronics, high power

|

Daily cycling, solar/RV/marine, long-life needs

|

Budget builds, low cycling frequency, simple setups

|

Regular Paragraph Section: How to Decide in Real Life

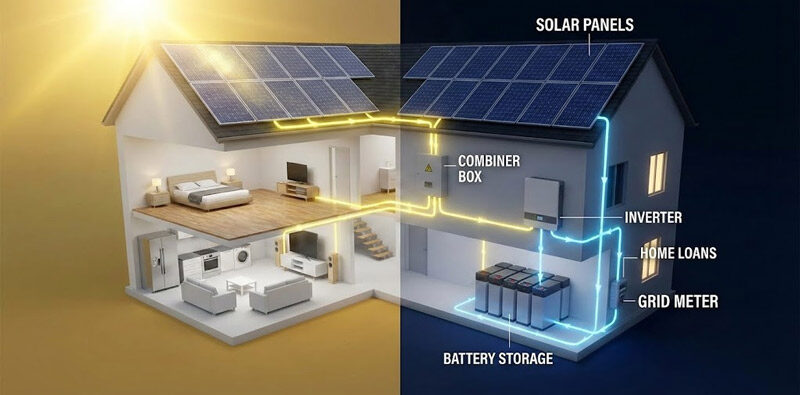

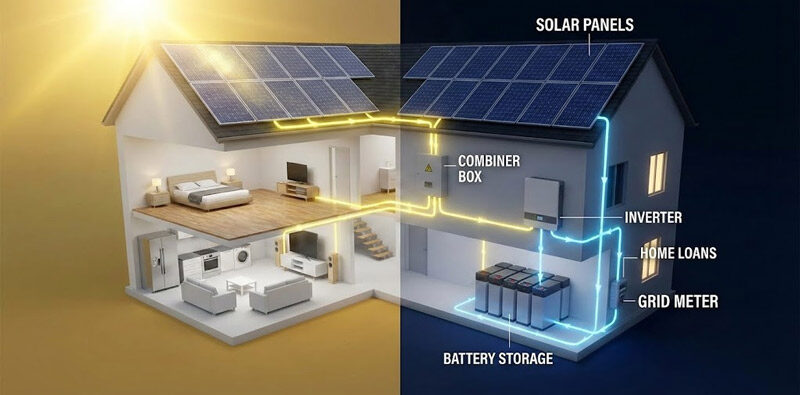

If your application involves frequent cycling—meaning you charge and discharge the battery often—lithium usually wins. This is because cycle life, efficiency, and usable capacity dominate the total value. For example, in a solar storage system, a lead-acid “high capacity” setup may appear affordable, but you may be forced to oversize it to avoid deep discharges. You also lose energy to charging inefficiency and face earlier replacement. A lithium battery, especially LiFePO₄, is often the “buy once, cry once” option: higher initial expense, but fewer headaches and a longer service life when used correctly.

If your application is rarely used—such as a backup battery you discharge only a few times per year—then a “high capacity” option that is not lithium can make sense, especially under tight budget constraints. In these cases, the shorter cycle life may not matter because you simply are not cycling it much. The decision becomes more about safe storage, maintenance needs, and whether you can accept extra weight and slower charging.

If you are weight- or space-limited, lithium is typically the better answer even if you can find a cheaper “high capacity” battery in another chemistry. A heavy battery bank can create physical constraints: mounting, transportation, structural load, and reduced mobility. Lithium’s high energy density can simplify the whole design and reduce total system weight dramatically.

However, it is a mistake to treat “high capacity” as automatically better. Capacity is only one part of battery performance. A large battery that can’t safely deliver the power you need, or that drops voltage so much that your device shuts off early, will disappoint. Likewise, a battery that provides impressive capacity on paper but only 40% is practically usable for decent lifespan is not truly giving you the energy you think you bought.

In most consumer and prosumer scenarios, the best approach is to define your needs using watt-hours, expected discharge rate, and number of cycles per year. Then compare options by cost per usable watt-hour over the battery’s expected life, not just sticker price or rated amp-hours. That framework makes the choice clearer and avoids marketing traps.

Bullet-Point Section: Practical Guidance and Scenarios

When a Lithium Battery Is Usually Better

-

Daily or near-daily cycling (solar storage, RV living, marine house banks, mobility devices).

-

High power draw (inverters, power tools, e-bikes) where voltage sag matters.

-

Portability and weight sensitivity (camping power stations, drones, robotics).

-

Fast recharge needs (worksites, travel, limited generator runtime).

-

Total cost of ownership focus (you care more about lifespan and performance than upfront price).

When a “High Capacity” Non-Lithium Battery Might Be Better

-

Lowest upfront cost is the top priority and replacement is acceptable.

-

Infrequent use (emergency backup, seasonal gear used a few times a year).

-

Very cold environments where your plan relies on simpler cold behavior (though capacity still drops in cold).

-

Simple, legacy charging systems that are designed around lead-acid and you don’t want to upgrade controllers/chargers.

Key Questions to Ask Before Buying

-

How many watt-hours do I actually need per day?

-

What is my peak power draw (watts), and for how long?

-

How often will I cycle the battery each year?

-

Do I need rapid charging?

-

What are my temperature conditions during charging and storage?

-

Do I have the right charger/controller for the chemistry?

-

Am I comparing “rated capacity” or “usable capacity”?

Quick Rule-of-Thumb Decisions

-

If you cycle >100 times/year, lithium is usually worth serious consideration.

-

If weight/space is a major constraint, lithium typically wins.

-

If you only need occasional backup and budget is tight, a high capacity lead-acid solution can be sufficient.

-

If safety and longevity are top priorities in a stationary setup, LiFePO₄ is often a strong middle ground.

Conclusion: So, Which Is Better?

The question “What is better a lithium battery or high capacity battery?” is best answered like this: lithium is a chemistry choice; high capacity is a sizing choice. If you want high capacity, you can (and often should) choose a high-capacity lithium battery—especially when weight, usable energy, charge speed, and long-term value matter. If your goal is simply to get the most amp-hours for the least money today and you do not cycle often, a high-capacity non-lithium setup may still be practical.

Ultimately, “better” means better for your specific usage pattern. Define your required watt-hours, peak load, cycle frequency, charging conditions, and budget. Then compare based on usable capacity, lifespan, safety needs, and total cost over time—and you’ll land on the right battery, not just a popular label.

FAQs

“High capacity” labels are confusing—how can I verify real capacity and avoid inflated claims?

Do not rely on marketing terms alone. Verify capacity using measurable electrical data.

Check the specification sheet for nominal voltage × rated amp-hours = watt-hours (Wh).

Confirm whether the rating is measured at a stated discharge rate (C-rate) and temperature.

For online products, look for third-party test results and compare cell brand or model, pack configuration (such as 4S or 8S), and BMS current rating.

If a seller only advertises mAh without voltage or avoids listing Wh, treat it as a red flag.

How do C-rate and internal resistance affect performance even if capacity is high?

Capacity indicates how long a battery can run under light load, but C-rate and internal resistance determine how it behaves under heavy or sudden loads.

High internal resistance causes voltage sag, excess heat, and premature BMS shutdowns during surges.

Two batteries with the same watt-hour rating can perform very differently.

The battery with lower internal resistance and higher continuous and peak current ratings will feel stronger, run cooler, and deliver power more reliably.

Do I need a BMS for lithium batteries, and which BMS specifications matter most?

For most lithium battery systems, a Battery Management System (BMS) is essential.

A BMS provides overcharge and overdischarge protection, cell balancing, and current limiting.

Key specifications to match to your application include:

- Supported chemistry (Li-ion vs LiFePO₄)

- Continuous and peak current ratings

- Low-temperature charge cutoff

- Balancing method and balancing current

- Optional communication features such as Bluetooth or CAN

Can I mix different batteries to increase overall capacity?

Mixing batteries is generally risky and not recommended.

Different chemistries operate at different voltages and have different safe limits.

Even within the same chemistry, mixing batteries of different capacities or ages can cause uneven current sharing.

This often leads to overheating, early cutoff, or accelerated aging.

If capacity expansion is required, use identical batteries of the same model, age, and state of health, with proper fusing and symmetrical wiring.

What charging profile differences matter most when switching from lead-acid to lithium?

Lead-acid batteries typically use bulk, absorption, and float stages and benefit from float charging.

Many lithium chemistries do not require prolonged float charging and may be stressed by it.

When converting systems, confirm that your charger or controller supports lithium settings, including:

- Correct maximum charge voltage for the chemistry

- Proper charge termination behavior

- Adjusted or disabled float voltage

- Appropriate temperature compensation

- Sufficient charge current and wiring to handle faster lithium charging